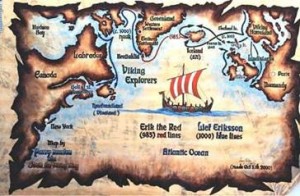

From around 800 onwards Ireland was attacked by bands of Viking marauders. The raids continued right through the 9th century and a second major wave began early in the 10th century. The monasteries, as the major centers of population ad wealth, were the main targets of the Vikings. They were despoiled of their books and valuables and many of them were burned. These attacks, and attacks by the Irish themselves contributed to the decline of the great monastic tradition at this period.

The Vikings were great traders and did much to develop commerce in medieval Ireland. They founded most of the major towns such as Dublin, Cork, Limerick and Waterford.

The Vikings were great traders and did much to develop commerce in medieval Ireland. They founded most of the major towns such as Dublin, Cork, Limerick and Waterford.

The lack of any political unity made it difficult to resist the Viking attacks. However, the strength of the Uě Nčill kings in the northern half of the country prevented the Vikings from establishing themselves there. Towards the end of the 10th century a new dynasty emerged in Munster in the south and, under the kingship of Brian Borů, was able to match the Uě Nčill. Brian Borů defeated the Vikings in 999 and in 1002 he won recognition as king of all Ireland. The Vikings intervened regularly in the disputes between the Irish kings. Their support for a Leinster revolt against Brian Borů led to their defeat at the Battle of Clontarf in 1014, after which they were confined to a subsidiary role in Irish political history.

The 11th and 12th centuries were an age of renaissance and progress in Ireland. Cultural activity and the arts prospered. It was a great era of religious reform and a powerful effort was made to bring the church more fully into line with Roman orthodoxy. Two of the principal figures of this movement were St. Malachy of Armaghand St. Laurence O’Toole of Dublin. In politics, others sought to follow Brian Borů’s example and establish themselves as kings of all Ireland. At various times between 1014 and 1169 the kings of Munster, Ulster, Connacht and Leinster succeeded in doing so. The general trend was towards the development of a strong centralized monarchy on the European model.

This trend was interrupted by the arrival of the Normans in 1167-1169. The first Normans came to Ireland from south Wales at the invitation of Diarmait Mac Murchada, king of Leinster, to support his ambition to become king of all Ireland. The leader of the Normans, Richard de Clare, known as Strongbow, succeeded Mac Murchada as King of Leinster. In 1171 the Normans’ overlord, Henry II, King of England, came to Ireland and was recognized as overlord of the country by both Irish and Normans.

This trend was interrupted by the arrival of the Normans in 1167-1169. The first Normans came to Ireland from south Wales at the invitation of Diarmait Mac Murchada, king of Leinster, to support his ambition to become king of all Ireland. The leader of the Normans, Richard de Clare, known as Strongbow, succeeded Mac Murchada as King of Leinster. In 1171 the Normans’ overlord, Henry II, King of England, came to Ireland and was recognized as overlord of the country by both Irish and Normans.

Thus began the political involvement of England in Ireland that was to dominate the country’s history in succeeding centuries.

The Normans quickly came to control three-quarters of the land. In time, they assimilated with the local population until they became, it was said, more Irish than the Irish themselves. The Normans had a major impact on the country. Throughout the 13th century they developed the same type of parliament, law and system of administration as in England.

However, the native, or Gaelic, Irish exerted pressure on the Norman colony. Outside the colony attempts were made to reestablish the native kingship. Edward Bruce, brother of the Scottish king Robert, failed in his attempt in 1315, the last serious effort to overthrow Norman rule. By the end of the 15th century, due to the depredations of the Irish and the Gaelicisation of the leading Norman families, the area of English rule in Ireland had shrunk to a small enclave around Dublin known as the Pale.